The stupid thing about innovation…

admin

- December 2, 2016

“Just be innovative, for once! Don’t keep suggesting the stuff that nobody wants!” The department manager rants at his team and they cringe, avoiding eye contact with their boss and pretending to be in deep thought. When he leaves the room the air fills with relief. Once again the team failed to meet his expectations. Nobody knows what these expectations are, exactly, and there is a feeling in the room that their manager expects the impossible: something the world is waiting for, something that will change people’s lives, something that will turn an industry upside down.

But even if you could come up with such a genius, ground-breaking idea, what would you do with it then?

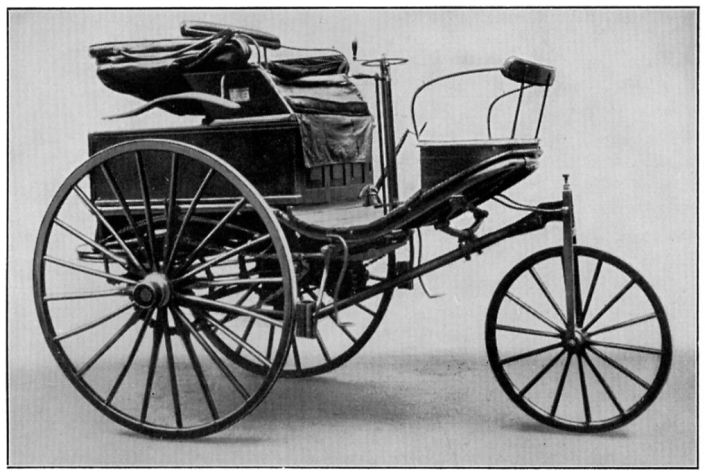

Carl Benz had such an idea. The mechanical engineer and motor developer had it in his head to build carriages which would drive on their own. Without being pulled by horses! In the 1890s, this was inconceivable, and his trial runs through the German city of Mannheim elicited mostly pity and shaking heads. Hardly anyone believed in Carl’s idea, not even the board members of his company. Carl Benz had his back up against the wall. He knew his idea would work, but he couldn’t get anyone to believe in it. His genius idea and development were worth nothing by themselves.

The stupid thing about innovation, then, is that it’s not enough to get your idea on the road. (Literally in Carl Benz’s case). You have to sell the idea, have people gather around it, root for it, get excited about it.

Carl Benz’ wife Bertha recognized this problem. Her husband needed a campaign, a storytelling format, to get at all the doubters and flouters. So she and her sons mounted Benz Motor Wagon Number Three and made the trip from Mannheim to Pforzheim (roughly 65 miles). There was no Autobahn in those days, so they had to drive on narrow forest roads. Sometimes the boys had to jump off and push. The city apothecary in Wiesloch became the first gas station in the world, because the pharmacist had ligroin (petroleum ether) in stock. Bertha Benz reached her goal, in both regards: she made it to Pforzheim and, by doing so, she proved that the one-cylinder vehicle developed by her husband had the potential to change the world.

The story of this first successful journey by motor carriage—and the world’s first female driver–spread like wild fire, and it convinced people that the horseless motor carriage was not only viable but had the potential to change the world. Without his wife’s marketing talents, Carl Benz’s idea may have failed.